When it is all over you will not regret having suffered; rather you will regret having suffered so little, and suffered that little so badly.

Blessed Sebastian Valfrè

I came across the above quote a few years ago, while recovering from a depressive episode, and was at once bewitched. Those words by a seventeenth-century Italian Catholic priest presented to me a refreshing angle from which to view my own struggles. If one could suffer “badly”, as Valfrè wrote, then conversely one could suffer well. But how?

That was the question buzzing in my subconscious when, as my friends went around the table sharing our new year resolutions, I’d said, “Honestly, I just want to learn to live a little more gracefully.” The year was 2017, and I was entering into the second half of my twenties feeling rather battered. By then, four years had passed since the first mental health crisis that turned my life helter-skelter.

I was, at the time, a bright-eyed international student in America, gamely juggling a near-perfect GPA and a packed social calendar. I had no way of knowing that I was also skipping closer and closer towards the precipice of a total mental breakdown.

Most people knew me as a calm, poised, and articulate young lady—I took pride playing that role. But that “Karen” was unceremoniously replaced by a paranoid, desperate, and hysterical understudy. Instead of rising early to make tea before any of her housemates arose, I would wake up a frozen shell, paralysed by the dreadful disappointment of still being alive. Rather than seamlessly weaving in and out of study parties and pub trivia nights, I would vanish and leave my friends’ frantic texts and calls unanswered. Once, my boyfriend found me flat on the floor of the library bookstacks, feverishly sobbing about being “the most pathetic person in existence”. On another occasion, my roommate found me wandering aimlessly around campus, stone-faced and mumbling about how good it would be to be a human vegetable. Yes, I was in pain, but I also suffered that pain oh so poorly.

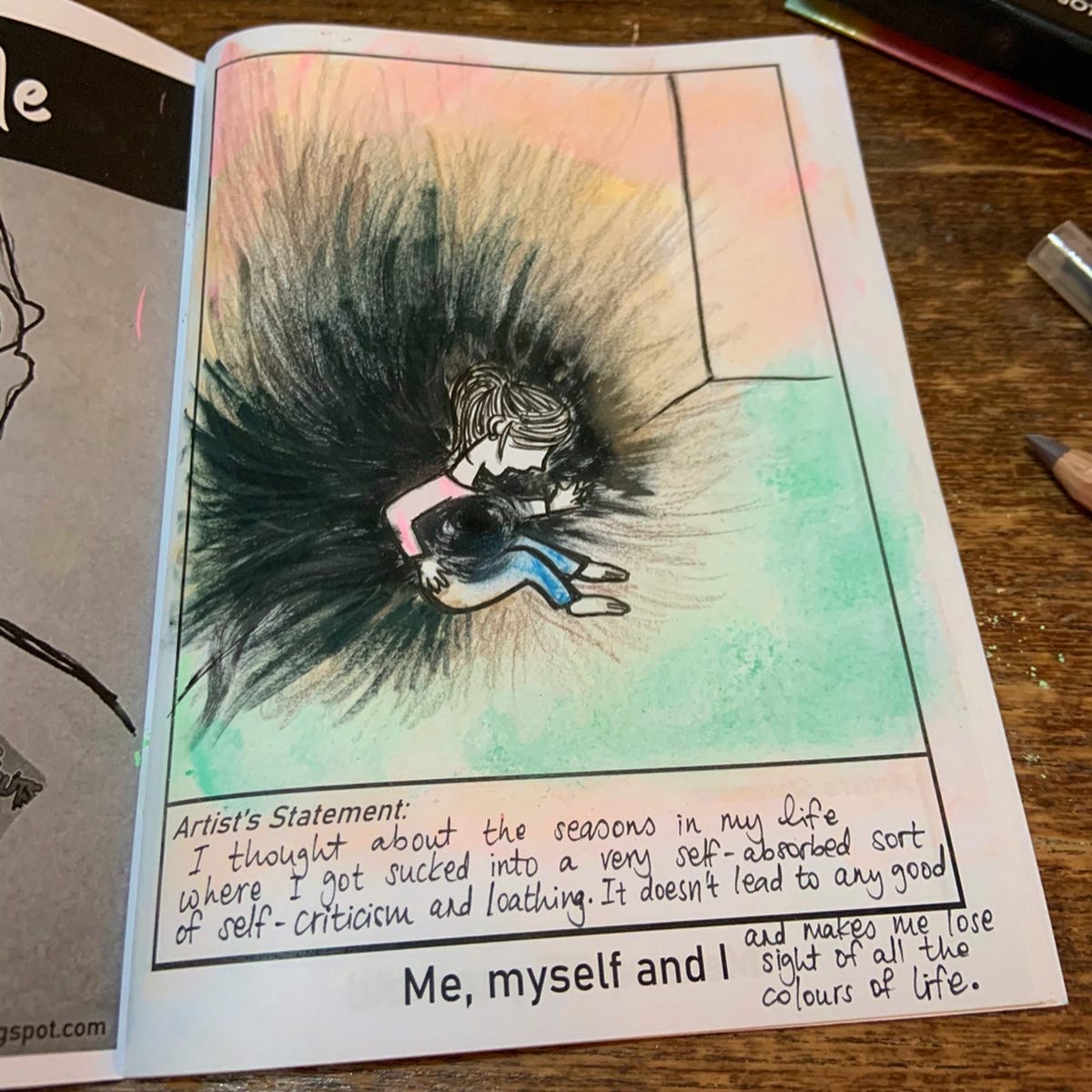

I eventually emerged refreshed and humbled, but when depression returned less than half a year later, I went back to being a black hole that threatened to suck my loved ones into my misery. It seemed certain that I would be stuck in this cyclical curse for the rest of my life.

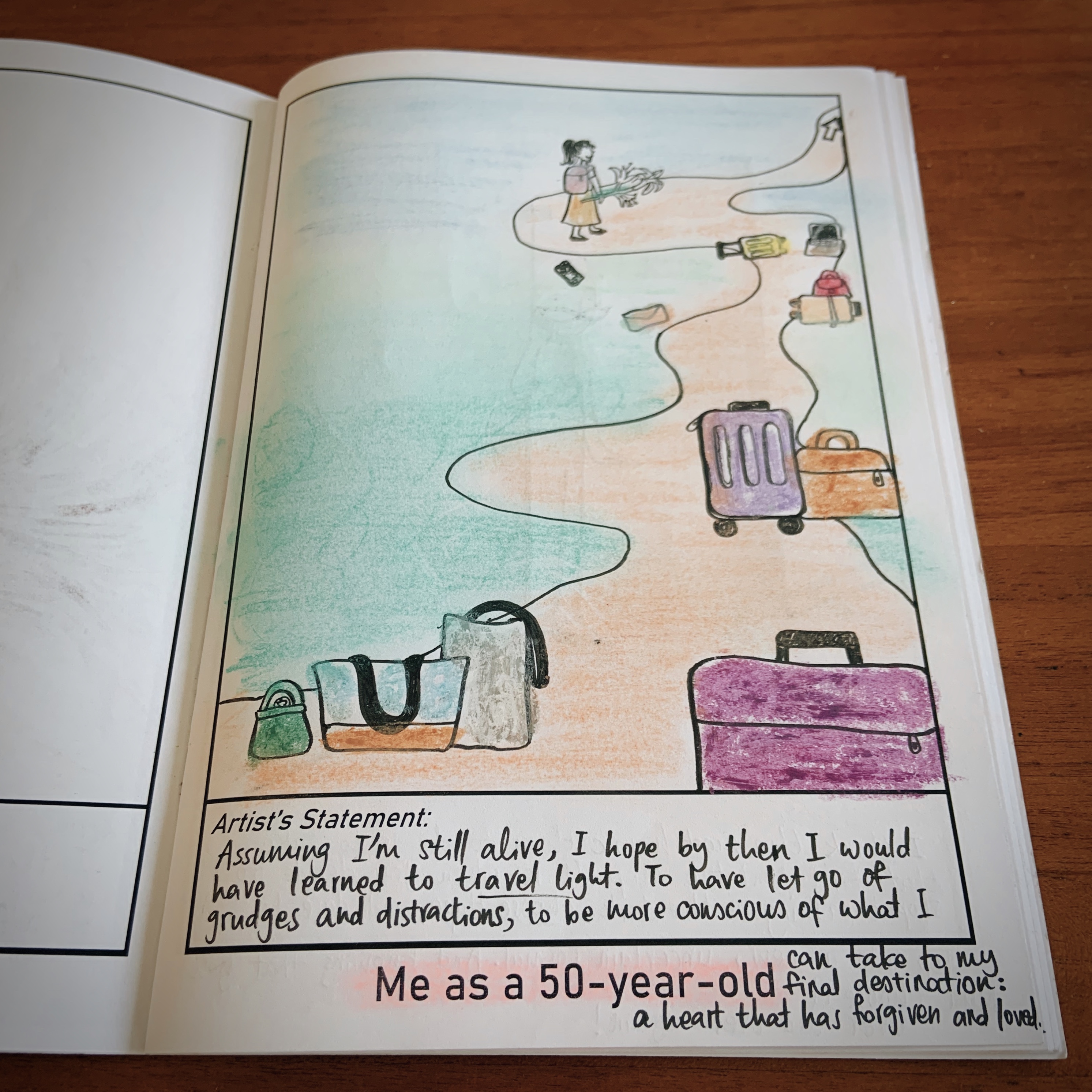

Yet here I am now in 2021, eight years after that very first episode, and I’m proud to say that I’ve made significant headway in my quest to be a “better” sufferer. These are six rules of engagement I’ve picked up along the way, which I hope can help someone else on their own journey:

1. First, accept that you cannot escape suffering.

I spent a great deal of my youth under the illusion that if I worked hard enough and smart enough, I’d have a good shot at eliminating suffering from my future. So invested was I in learning how to not suffer, that it never occurred to me to learn how to suffer. I was never afflicted with unemployment, poverty, disability, bullying, or cancer — or perhaps not yet — but into each lot some rain must fall, and what landed in mine was mental illness.

2. Understand that you do not have to do this alone.

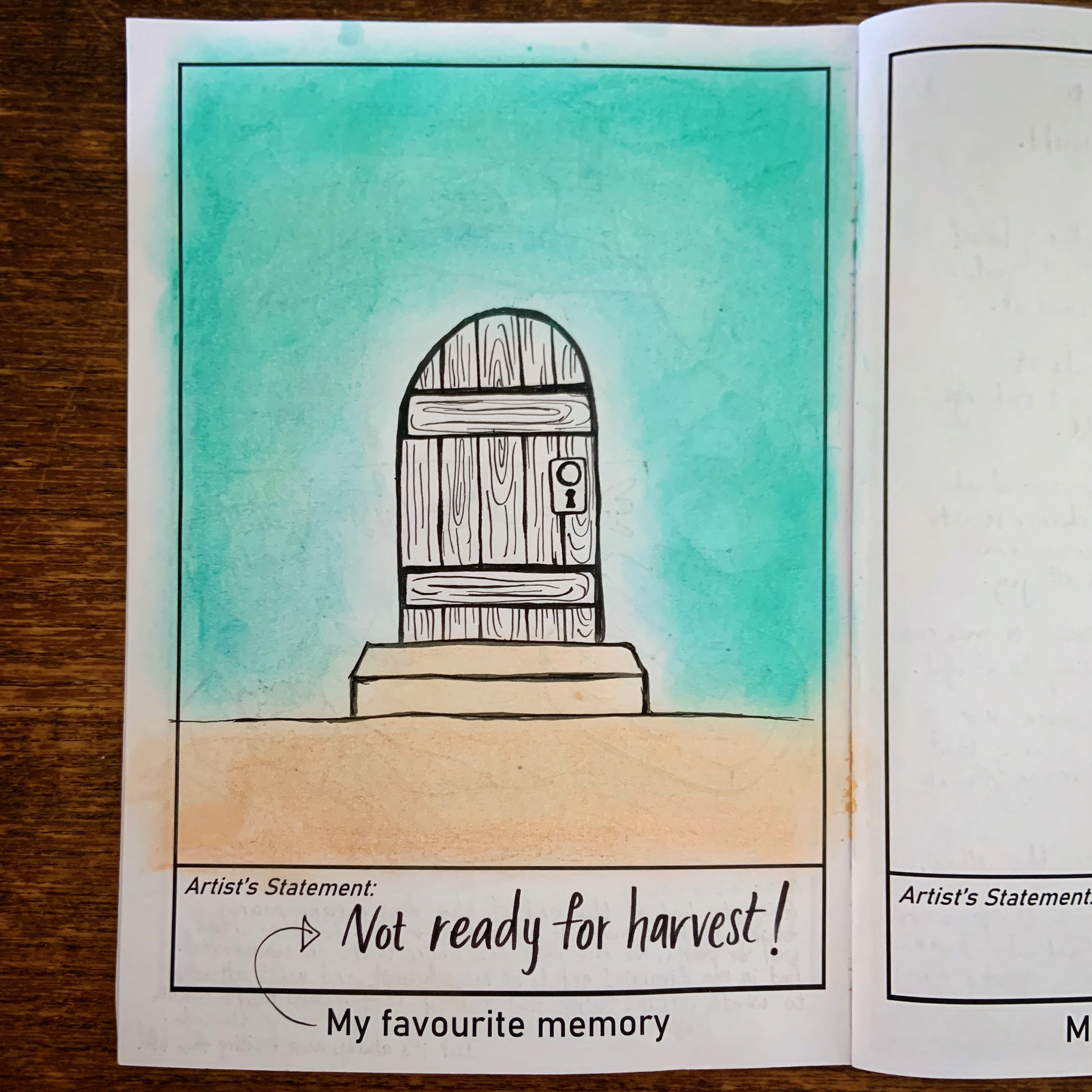

Recognising that depression was more than a one-time glitch, but potentially a recurring theme in my life was scary. Each time I recovered, I tiptoed around life fearing that the ground beneath my feet could crumble any moment, sending my hard-won sanity plummeting back to hell. It would be safer to not do or try anything, I thought, and give up all hope of the life I wanted to live. But the reason I saw no path forward was because it hadn’t been paved yet. With some help, brick by brick, this new path took shape. Help refers not only to psychiatry and psychotherapy, for most saliently it came in the form of heartfelt nagging by family members, blunt but loving conversations with close friends, electrifying memoirs and accounts of strangers who have suffered more gracefully than I… The more I was open to receive, the more solid the ground felt. And so I found my footing once more, along with the confidence to revisit old dreams and construct new ones.

3. Start small — learn to handle minor and mundane suffering.

In the beginning, I believed that the reason I suffered so poorly was due to the unbearable magnitude of my suffering. However, I came to realise as I recalled my growing years that I’d always had very poor tolerance for suffering of any degree—be it heartbreak, failure, rejection, fatigue, hunger, even humidity. I now know what seems to be so obvious: if you can’t suffer a little, you won’t be able to suffer a lot. Thus I secretly began to “train” myself. Sometimes this took the form of “elective” suffering, such as that period of time when I would opt to take the stairs instead of the escalator, or the time I abstained from my favourite iced milk tea for an entire month. I didn’t need to, but I just wanted to know that I could.

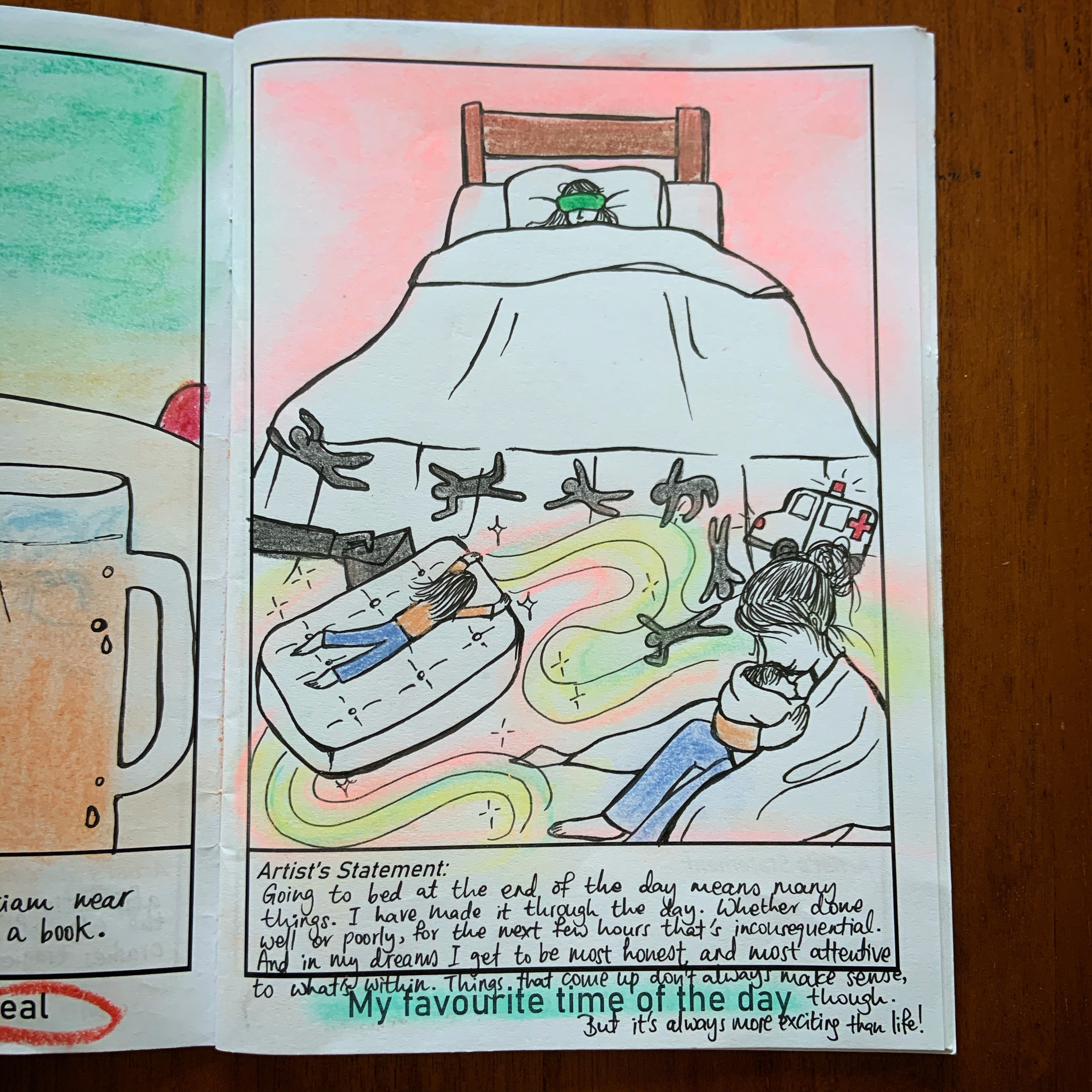

4. Take care of yourself as your would your own child.

This exhortation came from my friend Stephanie, who must have noticed that I hadn’t been feeding myself. I’d been consuming one meal a day, sometimes less; some days nothing. “Take care of yourself as you would your own child,” she texted one day, a peculiar phrase that gave me pause. I’d like to think I would feed my hypothetical daughter no matter how many mistakes she made; she would not cease to deserve it. And I’d speak to her not condemningly, but with a firmness tempered by gentleness. This sparked a journey towards self-compassion, and ultimately taking ownership of my pain. Learning to seek professional treatment independently, while a significant breakthrough, wasn’t enough. There’s a lot more I needed to do for myself and for the people I love: eat and sleep well, exercise regularly, be present for others, and simply keep moving.

5. Make room for laughter amidst your anguish.

Another one of my dearest friends, Manju, who had seen me through the earlier depressive episodes, told me one day that one of her favourite things about me was that I would break out in laughter even when crying. Again, a peculiar statement, and not the kind of compliment I would have sought in the past, but one for which I was grateful. Her observation made me realise another aspect of suffering gracefully: to allow joy to coexist with sorrow. In the earlier years, I would have been so adamant about the totality of my misery, and so obsessed with licking my own wounds, that I lost the ability to acknowledge anything good. To suffer well does not mean to never show grief or vulnerability, but to be able to partake in the joys of others even amidst pain.

6. Recognise in each painful moment an invitation to love.

I saved this one for last, as it cuts to the heart of everything I have been grasping for. All of the above would fall on deaf ears as long as one loses the will to get up. Why should I continue to bear with the pain if I had come to utterly despise myself? Eventually, I found my answer in Catholic theology: if I didn’t want to carry the “cross” for me, I could do it for someone else. There’s a phrase devout Catholics often use during unfavourable situations: “offer it up”. Instead of grumbling, offer it up. Rather than quit, offer it up. This means to intentionally offer up one’s pain or inconvenience as a sacrifice for the benefit of another soul. But one doesn’t need to be religious to appreciate the wisdom in turning our gaze outwards. (I, for one, wasn’t a Catholic at the time.)

While my brain told me I was utterly wretched and better off lying in bed all day, I could choose to focus instead on the people I lived with–a choice which got me out of bed to wash the dishes in the sink. When I felt the urge to send a barrage of despairing texts to my sister, I could choose to hold back and remember to ask how she was doing as well. However imperfectly, holding space for another person was a sacrifice I was still capable of making, a gift I was still capable of giving. A few years later, I was even able to keep my anguish in my pockets and stand tall as I emceed for a dear friend’s wedding, reminding myself that the best wedding gift I could give her was to set my pain aside for a day to welcome her joy.

These were all baby steps, but each one a powerful exercise in reconnecting with truth, goodness, and beauty even from a place of desolation.

To recognise in each painful moment an invitation to love, and to accept that invitation, that is to suffer gracefully.

Love that cannot suffer is not worthy of that name.

Saint Clare of Assisi

A shorter version of this essay was first published on The Tapestry Project SG – an independent, non-profit online publication that aims to restore hope and reclaim dignity through the sharing of first person mental health narratives.